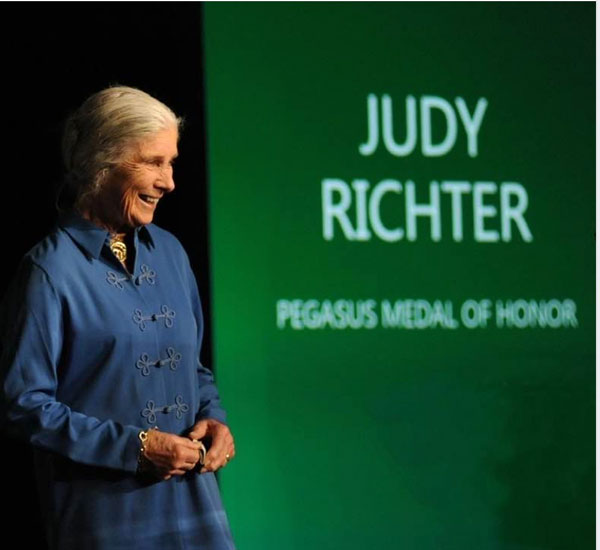

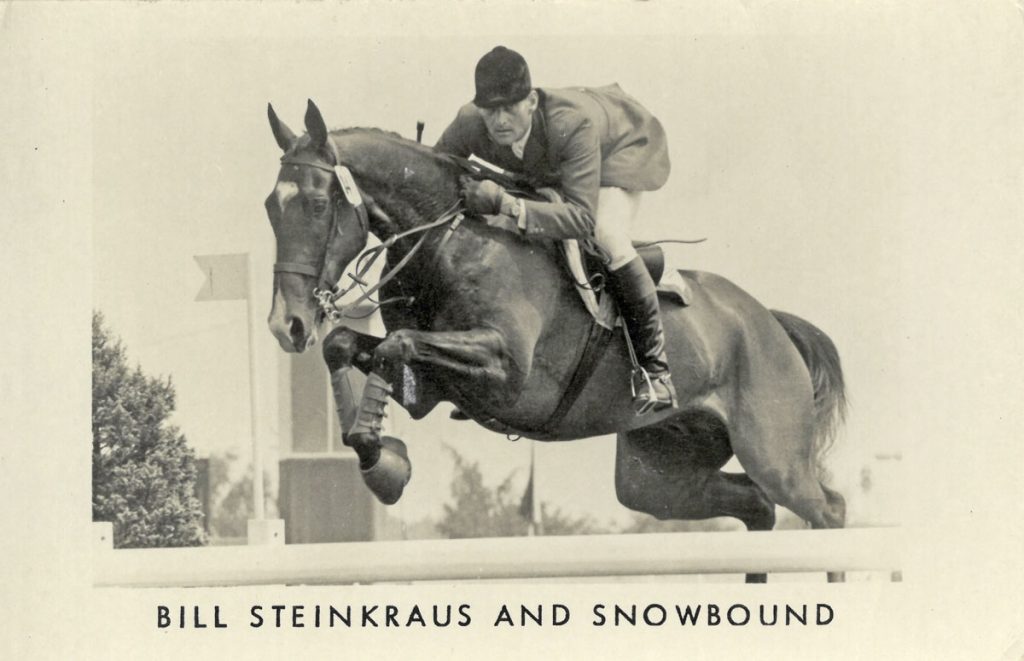

Rider, trainer, and author, JUDY RICHTER shares how celebrated showjumper William “Bill” Steinkraus uniquely influenced her life and career. Steinkraus inspired countless other riders over his career spanning several decades. Born in 1925, Steinkraus grew up in Darien, Connecticut. He learned to ride at age 10 from Amud Thompson and soon became a member of the Ox Ridge Hunt Club. Later, Gordon Wright and Morton “Cappy” Smith took him on as a student. The pair guided Steinkraus to victory at the coveted Maclay National Championship in 1941. Steinkraus’s legendary riding ability was equally matched by his innate love of horses. As a fastidious horseman and fierce competitor, his show-jumping career flourished quickly. The five-time Olympian held four medals in total to his name including the first individual gold to an American. Steinkraus earned numerous accolades as both a competitor and coach before his death in 2017 at the age of 92. —Emily Holowczak

Though a man of many interests and talents, Bill Steinkraus is best known as an American show-jumping champion. Having competed on our first civilian USET Olympic Show Jumping Team in 1952 to win the team bronze, he went on to win the individual Olympic Gold Medal in 1968 in Mexico City, the first American to do so.

An admirer of Bill since my preteens and his mid 20s, I watched him qualify at Fort Indiantown Gap, an Army outpost out in Pennsylvania, for our first civilian Olympic Team in 1950, and I was there when he won the individual Olympic Gold Medal in 1968 in Mexico City and many other major events before and after. I’m a lifelong fan.

Bill first came on my radar when I was a preteen and he was training with our newly formed civilian Olympic Show Jumping Team at Arthur McCashin’s farm, less than a mile down the road from our farm. Every day after school my younger sister, Carol, and I rode down there in hopes of getting a glimpse of the handsome group of our best riders. They rode in the morning, so usually they were nowhere to be seen. However we could often treat ourselves to listening to Bill practicing on his violin in the little cottage where he lived. That done, we would head for the polo field where there were countless jumps of all sorts, including a big bank and a waterjump. Since there was no one around to tell us we couldn’t, we jumped all their jumps every which way. We were lucky our horses were game and generous, if not great jumpers, and miraculously we survived. Even in their absence, Bill et al. raised our sights exponentially, and we made every effort to be around on Saturday and Sunday mornings to watch them ride and jump. He and the others were polite, but distant.

“Nice to see you,” and off they rode.That only upped their mystique. Soon they were off to indoors, the three big indoor horse shows in the fall—Harrisburg, Washington, and New York. Every year, we went to Madison Square Garden as often as we could to watch them. In between were the Olympics in Helsinki in 1952 where they won the bronze, proving to the world what we already knew: they were wonderful.

We were heartbroken when they moved to the newly established USET Training Center in Gladstone, New Jersey, 15 miles away. Too far to ride after school, and we didn’t drive yet, so we had to watch them from more of a distance. But our interest never flagged, as, led by Bill, they accumulated medals over the years. Even when my sister was on the Olympic team in the 1960s, Bill was still polite and distant whenever we encountered him.

In 1960 I was thrilled to watch him and Ksar d’Esprit jump seven feet to win the coveted Puissance class at the White City in London.

Fast forward a decade or so and Bill retired from International Show Jumping in 1972 to concentrate on his job as editor at Doubleday and raise his family. One day, out of the blue, he called me: Would I teach his children?…WHAT? Me teach his children? Besides the totally awesome request, the backstory is also important. In those days New York’s and Connecticut’s Fairfield and Westchester Counties were the epicenter of the equestrian world in America; the best trainers were all there with their fancy barns and indoor rings. I was on a cute little four-acre farm with a nice barn that could house six to eight horses and had no indoor ring. I carefully explained my situation, and he said it all sounded fine. Soon his three boys were coming with their ponies in a small van twice a week for lessons. Meanwhile, I sold him a wonderful pony, not a great mover, but he could jump, and high for a pony. Bill and I agreed the creatures had to jump high to spark the boys’ interest. The pony, Coplow Covert, sparked the middle son, Philip’s, interest and we had some fun showing locally at even major horse shows. (Fast forward 50 years and Philip still rides well.)

The lack of an indoor ring at our Coker Farm was easily solved; in the winter I rented an aisle for all our horses in the awesome Steinkraus stable with its more than adequate indoor ring. One of Bill’s Olympic steeds, Sinjon, was retired there. The favorite photo in my mind’s eye, for I had no camera on hand, was of Sinjon talking to my young, later to be extraordinary, jumper, Johnny’s Pocket, our horse of a lifetime. One day I worked up my nerve to ask Bill if he’d ride Johnny. Yes, and of course we all watched eagerly. I noticed that trotting to the right Bill consistently posted on the wrong diagonal. Finally I dared to ask him why and he said, “He prefers it.” Now there’s a horseman.

Another incident that winter, frightful as it was, revealed his character. One day, Ned, his youngest, arrived when I was in the midst of a lesson. He wanted to ride now, so I got one of my riders who was hanging around (They all did in those days), to saddle Ned’s pony and help him, which he did. Later I found out that afternoon they couldn’t find Ned’s saddle so they used Bill’s. Instead of wrapping the too-long stirrup leathers around the stirrups to make them short enough, they punched a bunch of holes in Bill’s stirrup leathers. They looked like Swiss cheese. Oh my goodness! How am I ever going to tell Bill? He will be furious. I knew how meticulous he was about everything. I stopped at a saddlery on my way home, bought the best leathers they had, and girded my loins to call him that evening. On the phone he was quiet and polite. I suspect he had already roared at Ned. He was tough on his boys.

Anyway, Bill offered to teach us how one properly punches holes in stirrup leathers. Soon thereafter we all gathered in his tack room to learn. With just a pen, a ruler, and a hole punch, he showed us how to measure lengthwise and sideways hole to hole. Not surprisingly, he was an excellent teacher. That day he was not just teaching about how to punch holes in our stirrup leathers, he was sharing his modus operandi.

Fast forward a few more decades, and wonder of wonders, we did become friends (and eventually he became a treasured mentor to my son, Philip), thanks to my good friend, Jimmy Lee, who needled me unmercifully to call Bill, so the three of us could have lunch together. “Let’s have lunch.” No, I couldn’t possibly do that. He wouldn’t want to have lunch with a couple of tongue-tied admirers like us. Finally I called, and he said yes, and thus began a wonderful friendship.

One of our last outings with Bill was to attend a celebratory dinner in Stamford, Connecticut, honoring all Olympic medalists who lived in Fairfield County. The USET called that morning begging Phil and me to go “to fill his table and clap appropriately.” They didn’t need to beg; Phil and I dropped everything and went. Besides honoring Bill, we looked forward to reconnecting with his three sons.

Over 100 admirers gathered in a fancy hotel to honor almost a dozen medalists: track and field, swimmers, etc. Each medalist spoke briefly and Bill spoke last. He held forth in his usual self-deprecating style: “My name is not a household word, unlike some of my predecessors tonight…” He described his sport briefly and pointed out that it was the horse that made it special, and why.

Looking toward the future, as he always did, he reminded us that the Olympics were becoming prohibitively expensive to hold, and he offered his solution, though clearly he knew it was flawed: hold the sports in venues that were already built. Though this would mean the Olympics would not happen at one venue, anything is preferable to canceling them altogether. Afterwards, he was the only speaker to receive a standing ovation. He was an eloquent speaker, and like everything he did, he did it well. It was probably Bill’s last standing ovation, and how appropriate that it came from fellow Olympians.

But it was more than that. All the people in the room recognized greatness when they saw it.