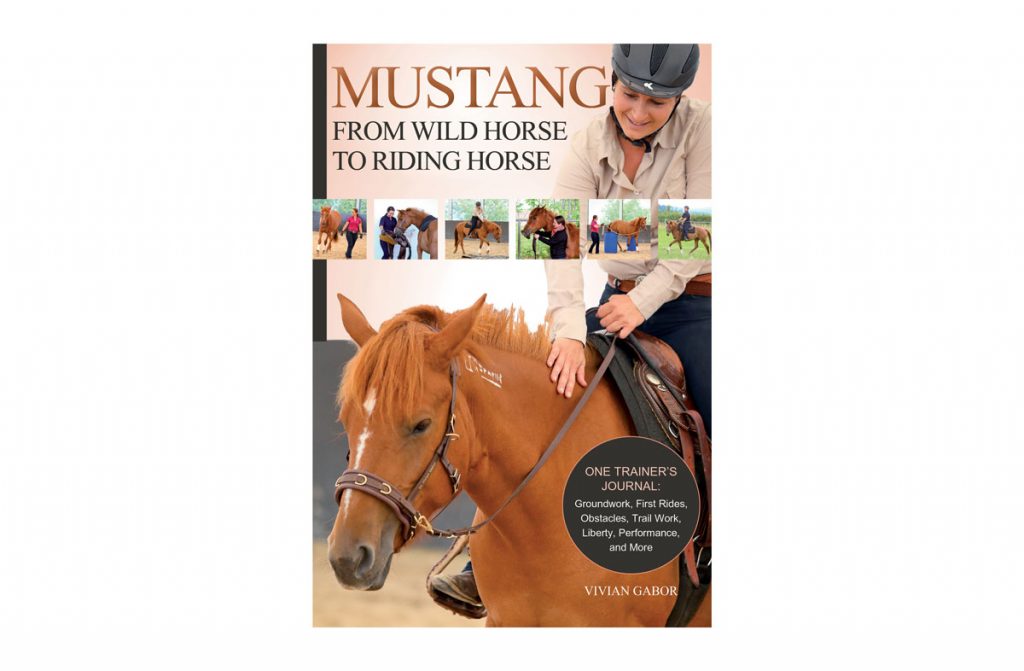

I feel excited as I catch sight of “my” Mustang for the first time, a brief first glance before the mare walks sweetly into the trailer. “She’s familiar with food rewards,” the organizer tells me. The trainer who prepared the Mustangs mentioned this to her specially. With a treat, the horse stands calmly in the trailer while the second horse is loaded. The back door of the trailer is then carefully closed, and I can travel home with a “wild horse” on board.

I am told that the American trainer had given my Mustang the name “Mona Lisa,” which in my mind becomes simply “Mona.”

I offer my Mustang mare the back of my hand and invite her to sniff it. Very hesitantly, Mona reaches her head in my direction. She is very cautious but also seems curious. The first, tentative touch happens!

I am still interested in connecting and go into Mona’s stall again; however, she doesn’t give me a friendly greeting. In fact, she doesn’t want me anywhere near her, and threatens me. I hadn’t expected that: skepticism, yes, but more evasive, even anxious behavior.

This first encounter and the mare’s defensive behavior have given me food for thought. Will I be able to convince this horse to work with me? I start having doubts. Make Mona “rideable” within three months? I don’t quite believe it yet. With these feelings, the first day with “my” Mustang comes to an end.

When I take Mona out for the first time, she follows me quietly for the 50 yards or so to the round pen, looks around, but definitely doesn’t go into flight mode. Everything is new to her: the buildings we walk between, the other horses in the exercise pen that she can see next to the round pen. Another 50 yards away is the large indoor arena—but this building doesn’t seem to impress her either.

I enter the round pen ahead of her and she follows me willingly. How do you begin training a wild Mustang? I try to see Mona as a completely normal horse and think about what I would normally do.

I start with some simple exercises that are supposed to teach her to focus on me. I walk in circles and keep stopping and observing whether she is paying attention to me. I can see that she finds this difficult and keeps looking around her. As a result, she follows unsteadily, a little behind me. You couldn’t call it normal leading. I notice that being led on a rope like this doesn’t mean anything to her. Of course, she just isn’t ready for it at the moment. And why should she be? I feel the urge to let her go. I consider for a moment whether that is wise, and what could happen. Our round pen is fenced with panels so, in principle, escape is impossible. It is possible that I won’t be able to catch Mona again. However, as has been the case with other timid or anxious horses, good round-pen training makes it possible to build up a relationship with any horse that allows himself to be caught again. (Well, that’s my theory, anyway.)

So I risk it and remove Mona’s rope. Then, something astonishing happens. I had expected her to want to get away from me. I am familiar with that behavior from horses I have trained, when I “let them go” in the round pen. They run around and try to get the lay of the land. But not this Mustang mare—she just stays next to me when I unclip the rope. It simply does not occur to her to leave me or to run wildly around the round pen. I can’t send her away from me. Instead, she is intent on staying by my side!

Nevertheless, I want to give her the opportunity to move away from me. That’s what I would normally do when training a young horse. One of the reasons I do this is to establish my status as the “leader.” The idea is that I determine speed and direction, and establish my position in the middle of the circle—in a space that the horse shouldn’t enter without being asked. If I see that the horse is attentive and relaxed, I bring him into the middle. Within a very short time, I have laid the foundations for respect and trust. The difficulty with Mona is sending her away from me.

I wonder how this can be possible as horses are supposed to be flight animals! I actually manage to send her into trot for at least a couple of yards then bring her back to me. She is soon following me freely for the first time after bringing her in the pen.

What a moment!

I try to touch Mona’s body more and more frequently. She doesn’t really like being touched. Why would she? She isn’t familiar with it. My touches don’t make any sense to her. Apart from another horse, what other animal would touch a horse in the wild? Contact with another species would only happen in an attack. If horses touch each other during mutual grooming, for example, this is always preceded by certain gestures. A horse will approach slowly and enquiringly, and mutual grooming only begins if the other horse consents. We take it for granted that we can just walk up to our horses and touch them. We should definitely think about this and realize what it means for them.

Mona shows me clearly that she doesn’t enjoy my touch, even if I approach her very cautiously. I assume that she can’t work out what the point is. Her expression changes and she quickly sends threatening signals in my direction. I don’t allow myself to be intimidated, but consciously relax and touch her shoulder-wither area with slow, stroking movements. I stop touching her as soon as her expression relaxes. The idea is to show Mona that she has a say in the decision and that I won’t force her to do anything. She should realize that acceptance and relaxation, not defense, are the solutions for influencing me.

I have been working Mona in the round pen without a rope or direct contact. Today, I want to try out this work at liberty in the arena for the first time. There is considerably more space for evasion in here, and it will become clear whether she already has a good bond with me because of our communication work—if she moves away from me, we still have to establish that connection. We start by walking over poles and through cones on the lead rope. I want Mona to focus on me. My praise motivates her, and I have a good feeling when I unclip the rope.

I stick with the exercises and start sending her through the cones at liberty. She gets verbal praise and a food reward after each time she walks through them. I also send her over the pole and she pays close attention to me. However, Mona also tries to find her own solutions and heads straight for the cones or the poles if I don’t give her a command and let her decide for herself. It is amazing to see how quick on the uptake she is! I obviously don’t want to encourage Mona to anticipate or even to demand food, but her cooperation and high motivation are wonderful to see. Her behavior is in no way pushy and anticipating food doesn’t make her stressed. I have seen some horses becoming stressed when they anticipate food and frantically reeling off behaviors in order to get a reward.

Yielding the forehand and hindquarters and lateral movement at liberty are also successful in the arena, and Mona has decided to stay with me during training. It’s a great feeling!

I send her through the cones around me in ever-increasing turns until we are doing our first circles of “free lungeing.” What this Mustang mare demonstrates after just a few sessions takes a lot of time, patience, and weeks of training in other horses!

Then it happens—once the work is done, Mona wants to roll in the fine sand of the arena, and I let her. She rolls luxuriantly in the sand, and then stays lying calmly there. I approach her cautiously, but she makes no move to get up. I start to stroke her head and neck and, for the first time, I feel that she is really enjoying it!

This genuine, relaxed, and calm togetherness lasts for minutes. It’s an incredible moment.

Adapted and used by permission from Trafalgar Square Books.