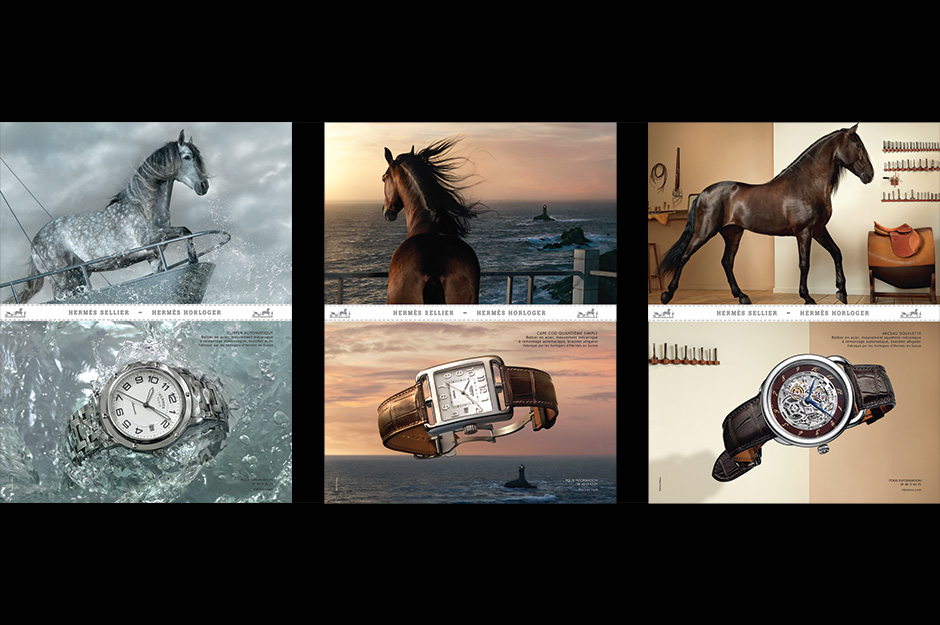

Tim Flach’s book Equus received awards and rave reviews from critics worldwide when it was published by Abrams in 2008. In it, the London-based artist/photographer celebrates the animal whose history is so powerfully linked to our own. From the exquisite Arabians of the United Arab Emirates to Icelandic horses in their glacial habitat, from the soulful gaze of a horse’s lash-lined eye to the thundering majesty of mustangs racing across the plains of Utah, Flach’s images provide a unique insight into the physical dynamics and spirit of horses everywhere.

Tim Flach was interview by EQLiving at his London studio in October of 2013.

What is your connection to the horse?

The horse is steeped around my family, every generation. My parents played polo and my mother hunted when she was younger. My grandmother even played polo in India. Iíd been looking at photographing animals, and it just felt that, as a subject, horses are inextricably linked with our culture. The earliest visuals in the caves of France were equine-related. Even before equitation and the domestication of horses, the horse was already so significant. To me, it was such a great subject to explore.

How did you decide what to photograph?

I wanted to explore the different cultures, but through the horses rather than the people. That was my clear distinction. I wanted to explore the landscape and the horse as an expression of the idea that a horse has been bred specifically by us and within different environments. I asked myself, ìWhat are the significant breeds?î And then I chose where to photograph them. I went to the United Arab Emirates and approached the Royal Yards, who were very cooperative. And then I worked with New Market here in England to look at race horses, then the very unique wild horses of Mongolia ó Przewalski’s horses, and so on.

There ís a natural tendency for people to have a particular interest in a certain breed or in a certain group of breeds. What I need to do as a visual person is to be aware of the tendency that people have to transform these images into meaning, based, of course, on their unique journey.

Do you have a preconceived photo in your mind, or a sketch, before you shoot?

I think that’s a very interesting question, and I think it is one that is fundamental to the creative process. How much do you plan and how much reveals itself to you during the creative process? Picasso spoke of his own work and said ìI don’t search, I find. You set up a situation: let’s go and explore an Andalusian, let’s say, to represent the idea of an Iberian Horse, or a Lusitano. And then when you get there, you’ve got these beautiful stallions with long manes. Then I spend some time and learn a bit about their behaviors, and I find out that, by using a carrot, I can end up with this thing that looks like a ball of mane. Itís about letting things reveal themselves, not being too prescriptive or presuming too much. I have a framework, but I have to be able to not just look, but to see.

When I photographed Icelandic horses, I showed the landscape of them going through ice floes. If you think about it, I would be missing a major trick, wouldn’t I, if I didn’t show the landscape. Not just because they are probably the most northerly kept horses, but also because there is a story behind the landscape: those horses are isolated. No horses can be brought into Iceland from outside, and no horse that has left can come back. So, you have 800 years of a bloodline import ban. To explore the idea of purity and genetics, and a specific type of movement of horse, it all goes back to the idea that the location was specifically unique to that breed. So, to not show them in their landscape would be to miss the plot, wouldn’t it?

After doing this, have you grown an affinity for any particular breeds?

I think I was more excited by people’s passion for their horses. When I was working with a zoologist in Mongolia, chasing wild horses across the landscape, with cowboys in the Rockies rounding up mustangs, or watching somebody showing miniature horses, I was excited by the individuals and their commitment, not so much by a particular breed. But there were breeds, like the Arabian, which I did feel an affinity for, because they’re so responsive, and they have so much importance as a progenitor of so many of the great breeds.